Floral foam – the facts

For the past 50 years it has been the most popular base floral design. However, as a single-use plastic packaging item, floral foam has no place in sustainable floral design. We explain what floral foam is and why it is such a problem for the environment.

Floral foam is at the base of flower arrangements all over the world.

Floral foam origins

Anybody who has worked in the flower industry will be familiar with the magical, green, water-absorbing blocks used to create flower arrangements.

First created in the 1950s by an American company Smithers-Oasis, floral foam soon became established as a useful packaging support and design medium for modern florists. But floral foam was not designed for purpose — it was a by-product from another industry that just happened to find a function in floral design.

The ultimate convenience

Floral foam is a remarkable product of great convenience. Not only does it hold up to 50 times its weight in water, but it can support a flower or foliage stem in a desired position and conduct water into the stem. It can be easily cut and shaped to fit into a container, and it is cheap to purchase, especially when compared with the cost of fresh flowers. As a packaging option, it makes transporting flower arrangements easier, keeping stems in place and preventing water spillage.

These features of floral foam enabled floral design to move in extraordinary directions as the process of arranging became simpler and faster, as well as allowing for more complicated design. Before the invention of floral foam, florists did their arranging straight into vases or pots of water, using chicken wire or metal pins under the water line to secure the stems in place.

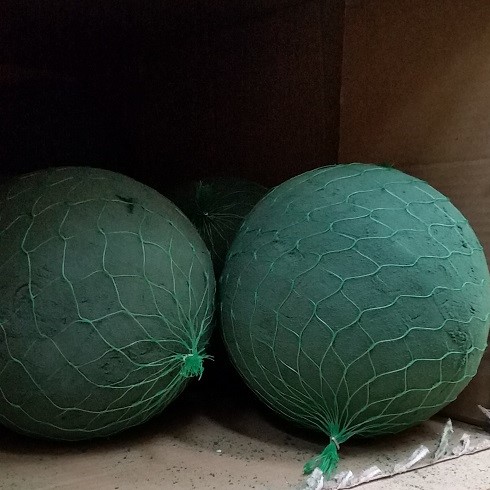

Wreath bases are usually made from floral foam.

Floral foam encased in a hard plastic guard used for funerals and event decoration.

What type of material is floral foam?

Floral foam is plastic.

It’s different to other families of plastics found in packaging and more familiar manufacturing. The most closely related product is a type of house insulation foam, but other plastics in this family include bakelite and the very hard resin found in billiard balls.

All these plastics belong to a group known as phenolic resins, or phenol formaldehydes. These were the very first plastics to be developed in the early 1900s.

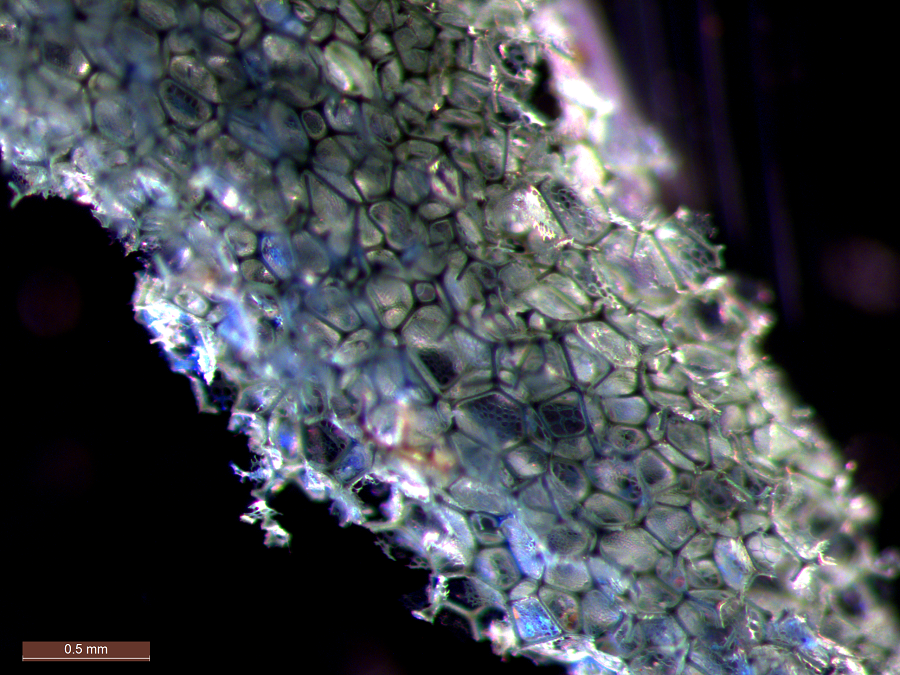

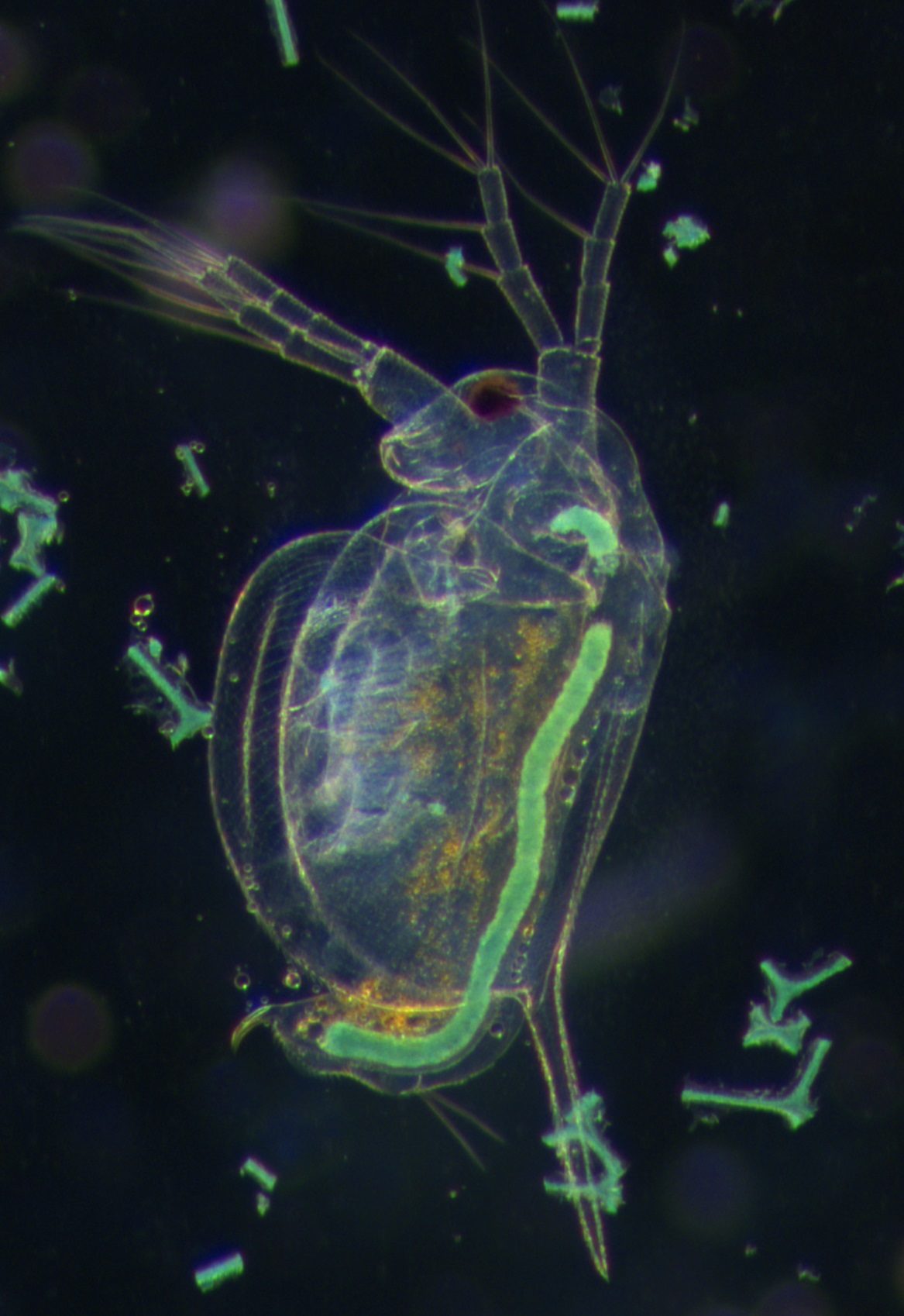

Floral foam under the microscope showing the cellular structure of the foam. Image: Dr Charlene Trestrail.

How does floral foam work?

Under a microscope, the structure of floral foam is very much like honeycomb, with spaces between the connecting chambers that allow water to move through the material. Floral foam is also very similar to the cellular structure in a plant’s stem.

Foam works by effectively becoming an extension of the flower’s stem. Before being cut, a plant receives water through the roots. However, when a stem is cut, water moves directly into the plant’s water vessels at the point where the cut has been made. This water is “pulled” up the stem by the action of water evaporating from the surface of leaves and the stem. Without water, the flower cannot open properly and will wilt and die.

This movement of water into a flower’s stem happens when a freshly cut stem is placed in a vessel of clean water, without foam. When the stem is placed in foam, the movement of water happens first through the foam and then into the stem.

The foam offers the added function of holding the stem in place. Although various claims are made about foam extending the life of flowers, one study found that floral foam can reduce the vase life of cut roses and concluded that “floral foam should not be used during the post-harvest handling of cut rose stems”.

Re-cutting a bunch of flowers and changing the water once or twice during the bunch’s vase life is a simple, chemical free way to prolong flower life. This action helps the stem to continuously take up water by keeping the water vessels open and preventing the build-up of bacteria, which causes the vessels to become blocked.

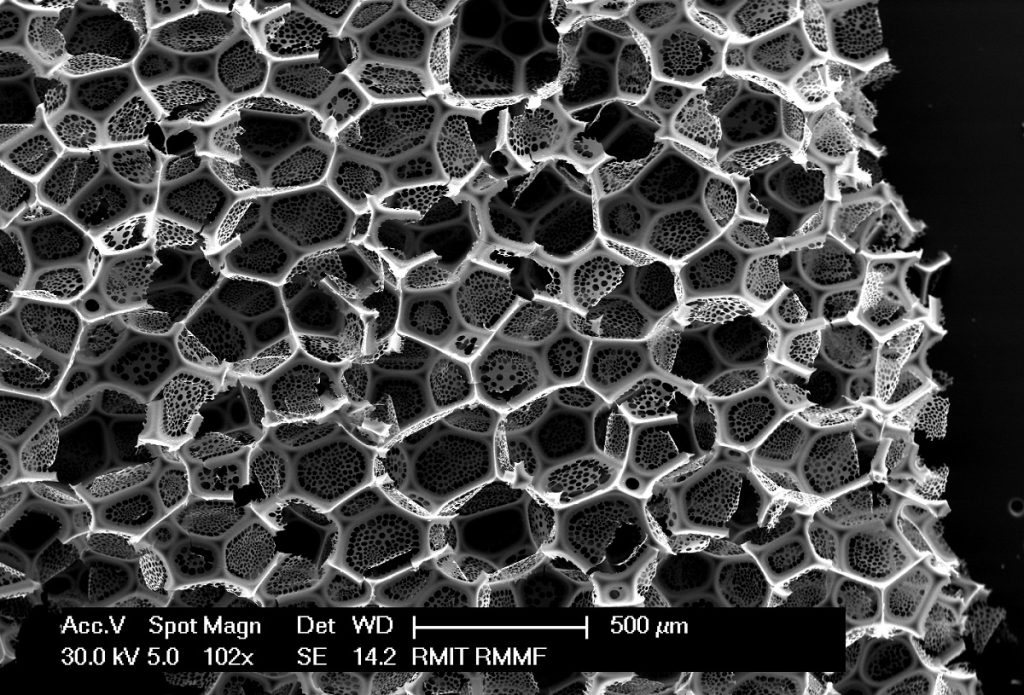

The honeycomb structure of floral foam enables water to move through the material easily. The structure of the plastic foam also means that the plastic fragments into tiny particles very easily. Image: Adam Truskewycz

Is floral foam biodegradable?

The short answer is no.

Biodegradability is the ability of a product to decompose as a result of microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. These organisms use the product as an energy source and break it down into simple compounds. The term ‘biodegradable’ is often associated with a substance being environmentally friendly. However, biodegradable products do not behave in the same way in all conditions. It is important to note that biodegradable and compostable are different things.

Plastics are typically not biodegradable, but they will eventually break down (over hundreds or thousands of years) or ‘degrade’ under other influences such as light, friction, heat or interactions with other chemicals in the environment. This process usually involves the material fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces first. Once they are smaller than 5 millimetres in size, they are commonly referred to as microplastics.

Because floral foam does not dissolve in water (it just breaks into smaller and smaller pieces), it must go through a process of degradation to break down. This can only go on at the surface of the plastic material. Floral foam already has a very large surface area where degradation can occur, even as a complete block, because of its cellular structure. However, while crumbling it into smaller pieces may help speed up the process, there is a downside because the microplastics are more easily dispersed in the environment where they can cause problems.

Floral foam crumbles easily into tiny fragments in water.

Floral foam microplastics from arranging flowers collect in vase water.

Floral foam crumbles when used and sticks to stems, making the plant material unsuitable for composting.

Floral foam microplastics - invisible to the naked eye. Image Prof. John West University of Melbourne

What is ‘bio floral foam’ or floral foam with ‘enhanced biodegradability’?

Manufacturers Smithers Oasis offer a foam product with ‘enhanced biodegradability’ known as Bio Floral Foam in Australia and the United Kingdom.

Bio Floral Foam is a plastic foam, with “an additive that attracts microbes”. The microbes use the additive as an energy source and degrade the block into smaller pieces.

The problem is that being biodegradable does not make plastic better for the environment – in fact, some fragmentable, ‘biodegradable’ plastics will be banned in Australia in 2022 because they are considered the most problematic of all.

“Products like this can be even more damaging if they end up in the environment as they turn into microplastics faster,” says Dr Thava Palanisami, a lead researcher on microplastics at the University of Newcastle, Australia. “The problem is that if the particles are released in the environment, they will not meet the conditions needed to completely break down the plastic, and the material can be taken up by animals in the original form.”

A recent independent study about the impacts of floral foam on aquatic animals by a group of researchers at RMIT University in Australia demonstrated that the “biodegradable” Bio Foam manufactured by Smithers Oasis is very similar in chemical composition to regular floral foam. It was also shown to leach more toxic compounds into the water than regular foam.” The study also showed that the material was eaten by aquatic animals with a range of feeding habits and that it is harmful for their health.

Bio Foam manufactured by Smithers Oasis is very similar in chemical composition to regular foam. Bio Foam also leached more chemicals into the water than regular foam, which can affect water quality in the environment and cause toxicity to animals

❝ — Dr Charlene Trestrail, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

Despite claims made about the product’s biodegradable properties, it does not meet US Federal Trade Commission requirements to be certified “biodegradable”. In the US, to be ‘certified biodegradable’, the “entire product or package will completely break down and return to nature, i.e., decompose into elements found in nature within a reasonably short period of time (one year) after customary disposal.”

Customary disposal in this instance is landfill. It is important to understand that these products have been designed for disposal in landfill only – not in soil, aquatic environments, compost or green waste.

Likewise, the product does not meet the European EN 13432 standard for biodegradability, which requires 90% of the material to be converted by microorganisms (biodegradation) in less than six months.

Dr Palanisami confirms that the product does not meet Australian Standards for Biodegradable Plastic either.

“In Australia, to meet current standards of biodegradability, a plastic product must breakdown completely in either home compost or industrial composting conditions, and also pass the worm toxicity test,” says Dr Palanisami.

Smithers Oasis Maxlife and Midnight Floral Foam

In the United States, Smithers Oasis’s “enhanced biodegradable” products are called “Floral Foam Maxlife” and “Midnight Floral Foam Maxlife”. The company recently announced that the products are “certified by Intertek to biodegrade up to 75 percent in one year”.

Intertek is an independent testing laboratory. Using the European Standard ‘EN 13432’ testing process to measure the rate of decomposition, Intertek determined that the product takes one year to break down 75% in oxygen-free environments.

However, the EN 13432 Standard requires compostable plastics to disintegrate after 12 weeks and biodegrade after six months to meet certification standards. Additionally, the by-products cannot have a negative impact on the compost produced.

Bio Floral Foam has been found to produce more toxic phenols than regular foam. It should never be placed in green waste or composting systems - it is only suitable for landfill disposal.

Bio Foam has been designed for landfill disposal only. It should never be placed in green waste or composting facilitiies.

Is floral foam toxic?

Floral foam is made from two chemicals considered to be hazardous to humans: phenol and formaldehyde.

These substances are mixed with non-hazardous substances to produce the final product.

The final product is not considered to be particularly toxic to humans under normal conditions of use, because the chemical composition changes during manufacture and the toxic components are at such low concentrations.

However, a recent independent study by RMIT University in Australia showed that floral foam is a problem for aquatic animals.

All animals in the study selected floral foam as a food source. The study showed that toxic compounds can leach out of the floral foam and into the surrounding water. Both consuming foam and being exposed to water surrounding floral foam particles was shown to cause harm to the aquatic animals studied.

Floral foam enters the natural environment when water containing foam is poured down a drain, the foam is discarded into a garden or soil, mixed with green waste or buried on top of a coffin.

A recent study looking at the impact on floral foam on aquatic animals showed that foam was consumed by all animals in the study. Image: Dr Charlene Trestrail.

Floral foam can harm animals by causing stress when ingested, and through exposing the animals to water containing toxins. Image: Dr Charlene Trestrail.

How to dispose of floral foam

According to an Australian-issued Oasis Floral Foam Safety Data Sheet dated 30th August 2019, the following advice is provided to users: Dispose in accordance with local regulations.

However, as yet, no regulatory bodies in Australia provide guidelines for the disposal of floral foam. Based on general disposal processes for plastic that is not recyclable or biodegradable:

-

All foam products should be sent to landfill-bound rubbish only.

-

Floral foam should not be placed in the compost, garden or in the natural environment.

-

Water containing foam fragments should not be poured down the sink or into storm water.

Contrary to advice supplied with earlier versions of some Safety Data Sheets, floral foam should never be crumbled into soil to improve drainage. This advice is not supported in any way by current scientific positions on the disposal of plastic waste and the urgent need to keep plastic out of the natural environment.

Pouring wastewater containing plastic foam fragments directly into stormwater (in gutters and drains by the side of the road) is the same as pouring it straight into the natural environment. Water here usually empties into the nearest watercourse and eventually makes its way to the ocean.

While a percentage of the solid matter poured down the sink will be captured through sewage processing, the reclaimed solid material from sewage treatment plants can be used to fertilise farmland. This action re-releases the plastic particles back into the environment where they can once again make their way into rivers and streams. Those particles in sewage not captured with solids will be released into the ocean with the post-treatment wastewater.

Best practice for disposing of water containing floral foam fragments

The best practice for disposing of water containing floral foam fragments is to pour it through a tight weave fabric such as an old pillowcase to capture as many of the foam fragments as possible. At this point in our understanding of microplastic and its impact on the natural world, best environmental practice would see this strained water poured into a hole in the ground or a garden to limit movement through the environment, but never the water system. However, it is important to remember that those plastic fragments will remain in that hole for an indefinite period of time.

With thanks to SFN Expert Advisors Professor Ian Rae and Dr Charlene Trestrail for their feedback and guidance in creating this article.